Considerations on System Design

Introduction

Designing systems, besides paying our salaries and stimulating the economy, regardless of where one is in the socio-economic chain—whether as an end user, partner, supplier, maintainer, or developer—has a primary goal of meeting a business need, genuinely based on the desire to fulfill a wish, such as accessing social media, listening to music, or investing in cryptocurrencies.

To materialize this desire, we use software engineering and its various disciplines. While software engineering applies engineering principles to the development, operation, and maintenance of software, software architecture proposes the high-level structure of a system, including its main components, their interrelations, and the principles and guidelines that guide its design and evolution.

System design is an essential and detailed part of software architecture. While architecture defines the macro vision and general principles, system design translates these principles into concrete implementations, ensuring that the system works as expected and meets business and technical requirements. To better understand the importance of this process, it is essential to analyze the fundamental role that software architecture plays in system development.

It is the process of defining the elements of a system, as well as their interactions and relationships, with the aim of satisfying a specified set of requirements. It involves taking a problem statement, breaking it down into smaller components, and designing each component to work together effectively to achieve the overall goal of the system.

Before we delve into System Design, let’s consolidate some concepts.

What is Software Architecture?

It is the fundamental organization of a system, expressed in its components, their relationships with each other and with the environment, and the principles that govern its design and evolution. In other words, it is the fundamental definition of components in a system and the principles that govern its design and evolution. These principles are the non-functional requirements.

They guide the choice of architectural components.

What is the Role of Architecture?

Software architecture plays a crucial role in the development of software systems, acting as a bridge between an organization’s often abstract business objectives and the resulting final system.

Decisions made during the architecture phase have a significant impact on the subsequent development, deployment, and maintenance of the system.

Here are some of the roles that software architecture plays:

Defining Structures for Reasoning: Software architecture defines structures that enable analysis and reasoning about the system. These structures encompass software elements, their relationships, and properties, and are essential for managing the complexity of a system.

Shaping Quality Attributes: The architecture of a system directly influences its quality attributes, such as performance, security, modifiability, and usability. Architectural decisions determine how these qualities are implemented and how the system will perform concerning them.

Guiding Implementation: Architecture serves as a guide for implementation, defining the system elements, their interactions, and responsibilities. This structuring facilitates task division, team communication, and ensures that the system is built cohesively.

However, for this guidance to be effective, it is essential to understand the importance of system design and how it contributes to avoiding common problems and ensuring the efficiency of software development.

Facilitating Communication among Stakeholders: Architecture provides a common language for project stakeholders, including developers, managers, testers, and clients. It documents architectural decisions, system components, and their interactions, allowing all involved to understand and discuss the system at a higher level.

Reducing Risks: Architectural evaluation anticipates and mitigates potential risks related to quality attributes, costs, and project schedule.

Software Design & System Design

While Software Design is responsible for the logical view of a system, it focuses on how the software is internally structured. It involves organizing modules, components, and defining their interactions to ensure that the software operates efficiently and is easy to maintain and evolve.

System Design, on the other hand, deals with the physical and operational view of the system. It involves defining the infrastructure needed to support the software, including servers, networks, storage, and other physical and virtual components.

Why is System Design Important?

It is not uncommon to find companies trapped by certain technologies or stuck in a never-ending cycle of migrations and adjustments, often buried under heaps of technical debt.

The reality is that the work of designing an architecture that adheres to the proposed problem is frequently not done adequately. Empiricism, bias, and trial and error tend to dominate in this scenario.

The point is that this costs time and money.

On the other hand, when architectural work is done well, empiricism, bias, and past experiences still play a significant role in defining the architecture to be followed. However, this is not necessarily negative.

In time, creating a robust architecture does not have to be excessively difficult. There is a wealth of literature, standards, and processes that condense knowledge, experiences, and widely tested and utilized architectures.

Using architectural patterns, as described in “Software Architecture in Practice,” can provide clear and proven guidelines for developing efficient and scalable systems.

These patterns and processes not only save time and money but also reduce the risks associated with software development. By leveraging best practices and accumulated knowledge, companies can avoid common pitfalls, such as over-reliance on a single technology or the accumulation of technical debt.

Therefore, instead of relying purely on trial and error, it is advantageous to adopt a more structured and informed approach, utilizing resources available in specialized literature and software architecture standards.

This not only facilitates the development of more effective solutions but also promotes greater sustainability and continuous evolution of systems.

To implement this structured approach, it is important to follow a well-defined architectural process that guides from initial analysis to the evaluation of proposed solutions.

Architectural Process in Software Engineering

The architectural process is a set of systematic activities aimed at defining the structure of a software system, identifying its main components, their interrelations, and the principles and guidelines that guide its design and evolution.

It serves as a bridge between high-level requirements and detailed implementation, ensuring that design decisions meet business objectives.

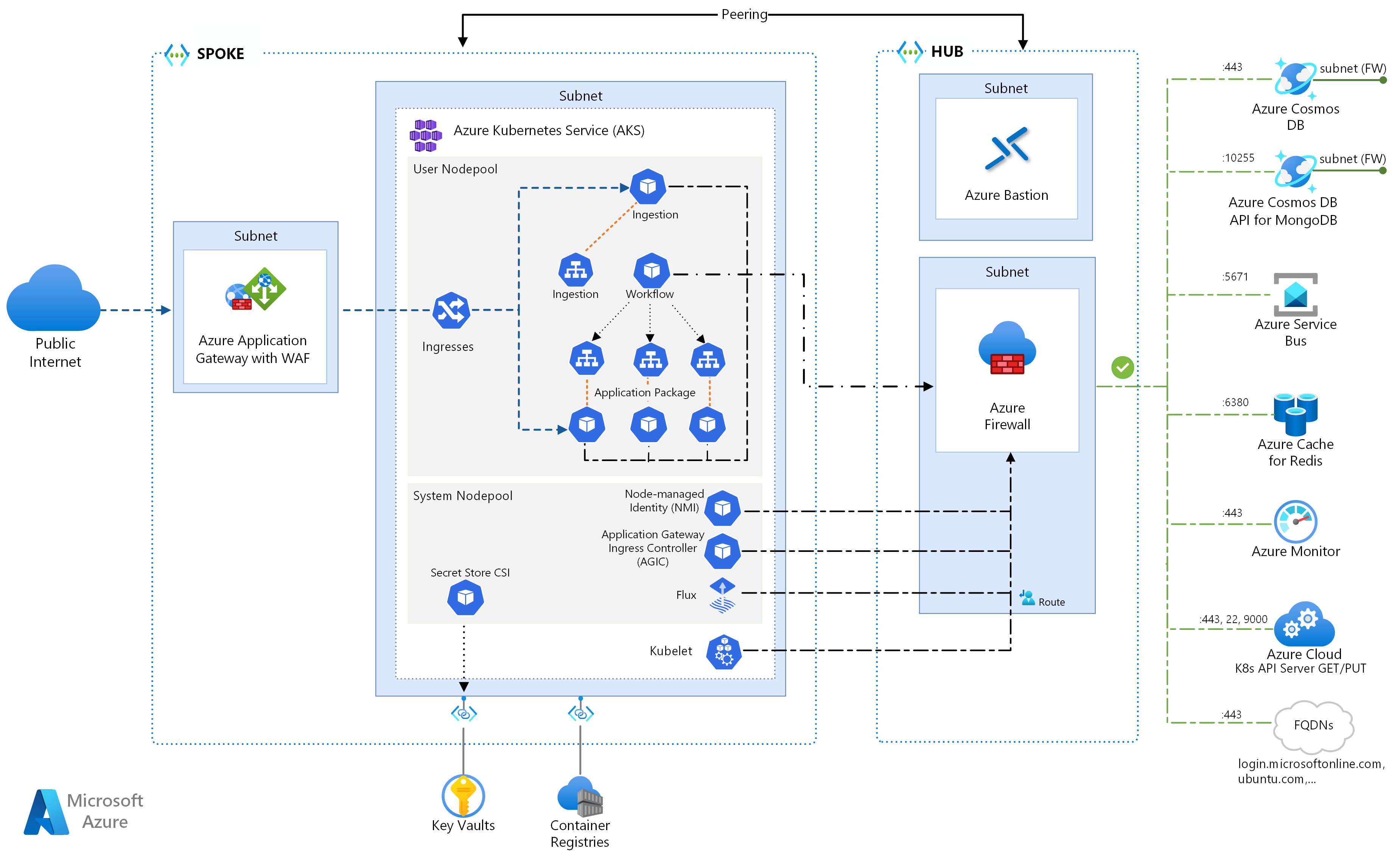

The architectural process can be summarized in the following diagram:

Architectural Process Stages

Architectural Analysis:

Objective: Identify and understand architecturally significant requirements (ASRs) and architectural concerns in the context of the system.

Description: During architectural analysis, architects gather and analyze crucial information about the system’s functional and non-functional requirements. They identify the critical issues that the architecture must address, such as performance, security, usability, and scalability. This stage involves a detailed understanding of the system’s context, constraints, and stakeholders’ expectations.

Input: System context and architectural concerns.

Output: Architecturally Significant Requirements (ASRs).

Architectural Design:

Objective: Develop candidate architectural solutions that address the identified ASRs.

Description: In this stage, architects create different architectural design options to solve the problems and meet the requirements identified during the analysis.

These solutions include defining the system structure, organizing components and their interactions, and selecting appropriate patterns and technologies.

Input: Architecturally Significant Requirements (ASRs).

Output: Candidate architectural solutions.

Architectural Evaluation:

Objective: Validate the candidate architectural solutions and identify areas for improvement.

Description: Architectural evaluation is conducted to verify whether the proposed solutions meet the requirements and expectations of stakeholders. This may involve reviews, prototyping, simulations, and testing. During the evaluation, areas for improvement and necessary modifications are identified to refine the architecture.

Input: Candidate architectural solutions.

Output: Improvement points/modifications to the architecture and validated architecture.

Execution Flow

The execution flow shown in the image highlights the continuous interaction between the stages of the architectural process:

From System Context to Architectural Analysis:

The process begins with gathering information about the system context and architectural concerns. These inputs feed into the architectural analysis.

From Architectural Analysis to Architectural Design:

The architecturally significant requirements (ASRs) identified during the analysis are used to guide the architectural design, where candidate architectural solutions are developed.

From Architectural Design to Architectural Evaluation:

The candidate architectural solutions are then evaluated to ensure they meet the requirements and expectations. The evaluation results in either a validated architecture or improvement points that require adjustments.

Continuous Improvement Cycle:

Architectural evaluation may identify necessary modifications to the architecture. These modifications are fed back into the architectural design process, creating an iterative cycle of continuous improvement until the architecture is validated.

To support this process, various tools and techniques may be employed to ensure effective communication and accurate documentation of the proposed solutions.

Essential Tools for the Architectural Evaluation Phase

During the evaluation phase of the architectural process, effective communication of the proposed solution is crucial. Architects use various tools to create diagrams, presentations, and documentation.

Diagrams

Diagramming tools such as draw.io and Excalidraw are very effective for creating visual representations of the architecture. These tools allow architects to document different views of the architecture, each addressing the specific concerns of various stakeholders. Here two awesome tools to build diagrams:

Whiteboarding

Whiteboarding is a valuable technique for group discussions and architectural reviews, especially during the evaluation phase. It enables real-time brainstorming and collaboration between architects and stakeholders, facilitating the identification of potential issues and validation of design decisions.

Here a cool example about it: Whiteboard with an SA: AWS Code Deployment

Architecture Decision Records (ADR)

ADRs are documents that record significant architectural decisions made during the design process. They provide a traceable history of the rationale behind architectural choices, aiding in the understanding and maintenance of the architecture over time. Each ADR typically captures the context of the decision, the alternatives considered, the decision made, and its implications.

Cloud Provider Cost Calculators

Cloud provider cost calculators are tools used to assess the financial implications of architectural decisions, particularly when considering cloud computing platforms. However, beyond tools and techniques, it’s important to consider quality attributes and non-functional requirements that directly impact the success of a software system.

Proof of Concept (PoC)

A Proof of Concept (PoC) is a preliminary implementation of a solution aimed at demonstrating its practical feasibility. Unlike a prototype, which is a simplified version of a final product, a PoC focuses on testing whether a concept or theory can be practically realized. It is often used in IT projects to validate new technologies, architectures, methodologies, or functionalities before proceeding with full development.

Now, we have a clearer understanding of what software architecture is, the processes and tools for building efficient system design, and we understand that software architecture proposes the high-level structure of a software system, including its main components, their interrelations, and the principles and guidelines that guide its design and evolution. We will discuss these principles in detail next.

Functional and Non-Functional Requirements

Although often treated as separate entities, the functional and non-functional requirements of a software system are intrinsically linked.

While functional requirements describe what the system does, including its features, services, and expected behaviors, non-functional requirements, or quality attributes, dictate how the system should perform in terms of performance, security, modifiability, usability, and other crucial aspects.

It is important to note that software architecture is not defined by functionality alone. In other words, for a specific set of functional requirements, there is an almost infinite range of possible architectures. The ideal architecture emerges from the need to satisfy both functional and non-functional requirements, and it is in the allocation of responsibilities to architectural elements that this synergy becomes evident.

The influence of quality attributes on architecture manifests in the choice of system structures and behaviors.

For example, the pursuit of high performance might lead to the adoption of a modular decomposition structure that minimizes communication between modules, while the need for security might require the inclusion of authentication and authorization mechanisms in critical interfaces.

Ignoring the interdependence between functional and non-functional requirements leads to systems with serious flaws. A system might perform all desired functions, but if it exhibits unacceptable performance, is vulnerable to attacks, or is difficult to maintain, it is doomed to failure.

Architecture, as the link between requirements and system, must be conceived with the understanding that functionality alone does not guarantee success.

Practical Example

Let’s consider an e-commerce system with the following requirements:

Functional: Product catalog management, shopping cart, order processing.

Non-Functional: High availability, transaction security, fast response time.

Implementation:

Product Catalog (Functional): Uses a microservices architecture, where the catalog is an independent service.

Transaction Security (Non-Functional): Implements SSL/TLS to encrypt data in transit and uses tokenization to protect payment information.

High Availability (Non-Functional): Employs load balancing techniques and deployments in multiple geographic regions to ensure the system is always available.

Response Time (Non-Functional): Adopts caching for frequently accessed data and optimizes database queries to improve response time.

Constraints During the Architectural Process in Software Engineering

Creating an effective software architecture is akin to navigating a maze of complex decisions. Each decision entails accepting constraints that shape the resulting system.

Far from being undesirable obstacles, constraints in the architectural process act as guides that direct decisions towards achieving the system’s goals, balancing functional and non-functional requirements (quality).

Sources of Constraints

Constraints in architectural development can originate from various sources, like:

Non-Functional Requirements (Quality Attributes): The pursuit of high performance, for example, imposes constraints on the choice of technologies and the communication structure between components. The need for security may restrict data access and require robust authentication mechanisms.

Functional Requirements: The very nature of the desired functionality can impose constraints on the architecture. For instance, a real-time system processing sensor data imposes constraints on response time and requires an architecture that minimizes delays.

Organizational Factors: Budget limitations, tight deadlines, availability of personnel, and technical expertise can restrict design and implementation options.

Technology: The choice of platforms, programming languages, frameworks, and libraries imposes constraints and shapes the system architecture.

Existing Constraints: In modernization or evolution projects involving legacy systems, the existing architecture imposes significant constraints on design decisions.

Impact of Constraints

When well understood and managed, constraints play a crucial role in the success of the architectural process:

Focus and Direction: Amidst a universe of possibilities, constraints help focus on critical aspects of the system and make more informed decisions.

Balance Between Quality Attributes: Constraints force the team to find solutions that address multiple quality requirements, avoiding designs that prioritize one aspect at the expense of others.

Risk Management: By recognizing and analyzing constraints from the outset, the team can anticipate challenges, identify potential risks, and take preventive measures.

Managing Constraints

Effective management of constraints is essential for successful architecture. Recommended practices include:

Identification and Documentation: Clearly recording constraints and making them accessible to all stakeholders ensures shared understanding and facilitates decision-making.

Transparent Communication: Maintaining open and honest dialogue between architects, developers, and stakeholders about constraints and their impacts is crucial to avoid surprises and conflicts.

Flexibility and Adaptation: Constraints may change throughout the project lifecycle. It is crucial to remain flexible to adapt to new realities and revise decisions when necessary.

Constraints, although often viewed as obstacles, are inherent and crucial elements of the architectural process. By embracing constraints as guides and adopting a proactive approach to their management, architects can make more informed and effective decisions, resulting in more robust, flexible software systems that align with stakeholder needs.

Non-Functional Requirements / Quality Attributes

In software architecture, the functionality of a system—what the system does—is just part of the story. To ensure the success of a system, it is crucial to consider how it performs its functions. This is where non-functional requirements (NFRs), also known as quality attributes (QAs), come into play.

While functional requirements describe the capabilities and behavior of the system, NFRs specify characteristics such as performance, security, availability, usability, modifiability, and many others. They define how well the system performs its functions, directly impacting user experience and project success.

Standards like ISO 25010 define a quality model for software products and systems. This model encompasses characteristics and features that describe the quality of the product and serves as a guide to identifying quality attributes in software systems.

Overall, ISO 25010 is represented as follows:

However, this list may not cover all cases and includes the context of the need, and it also expands to a very high level of granularity. Therefore, we will focus on two categories of quality attributes.

The first category includes attributes that describe some property of the system at runtime, such as availability, performance, or usability.

The second category includes attributes that describe some property of the system’s development, such as modifiability, testability, or implementability.

Thus, non-functional requirements or quality attributes can be understood as:

- Availability

- Deployability

- Energy Efficiency

- Integrability

- Modifiability

- Performance

- Security

- Functional Safety

- Testability

- Usability

Before diving into the details of what each attribute entails, it’s important to know that there is a standard behavior among attributes, where it is possible to measure them and understand their dynamics and relationships.

This is known as the quality attributes scenario.

Quality Attributes Scenarios

Defining non-functional requirements (NFRs), such as performance or security, in vague and abstract terms is a common issue in software projects. Stating that a system must be “fast” or “secure” does not provide concrete guidelines for design and development.

This is where quality attributes scenarios come in—a powerful technique for specifying and testing NFRs in a precise and useful manner.

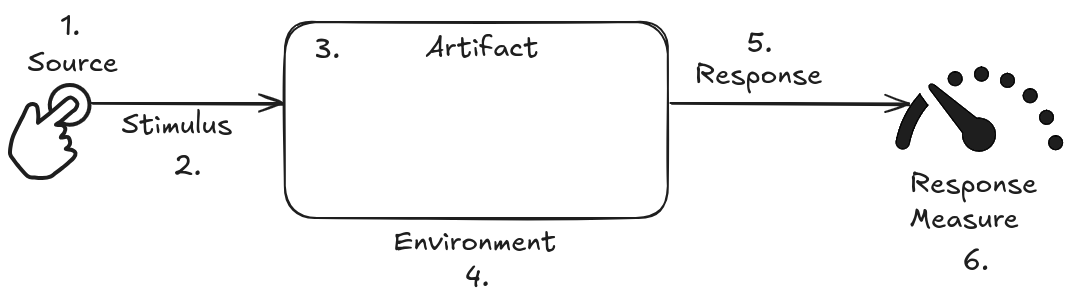

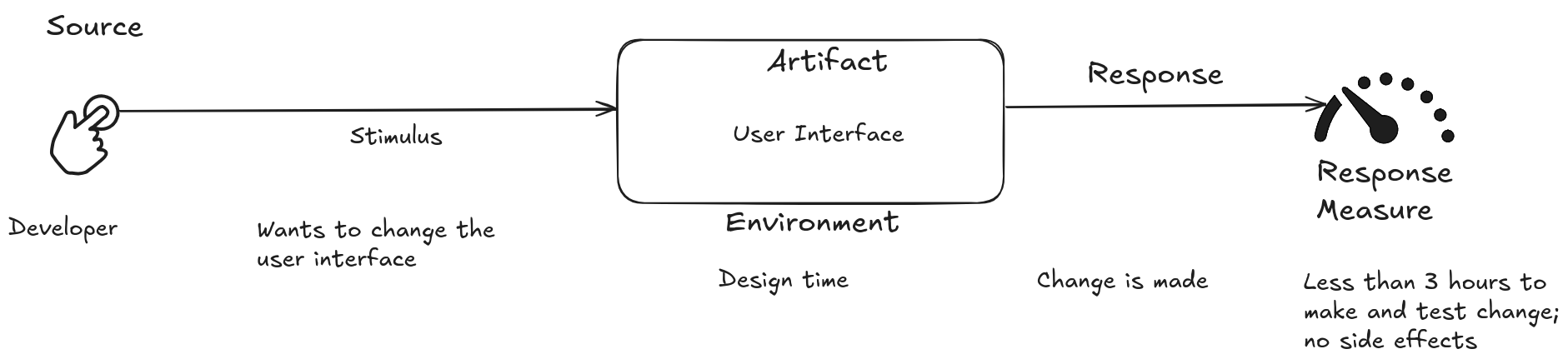

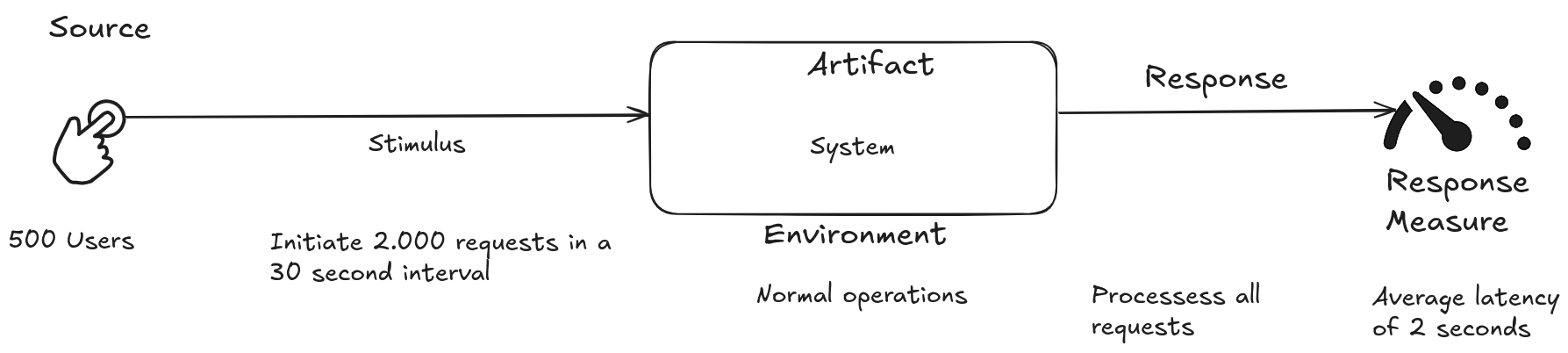

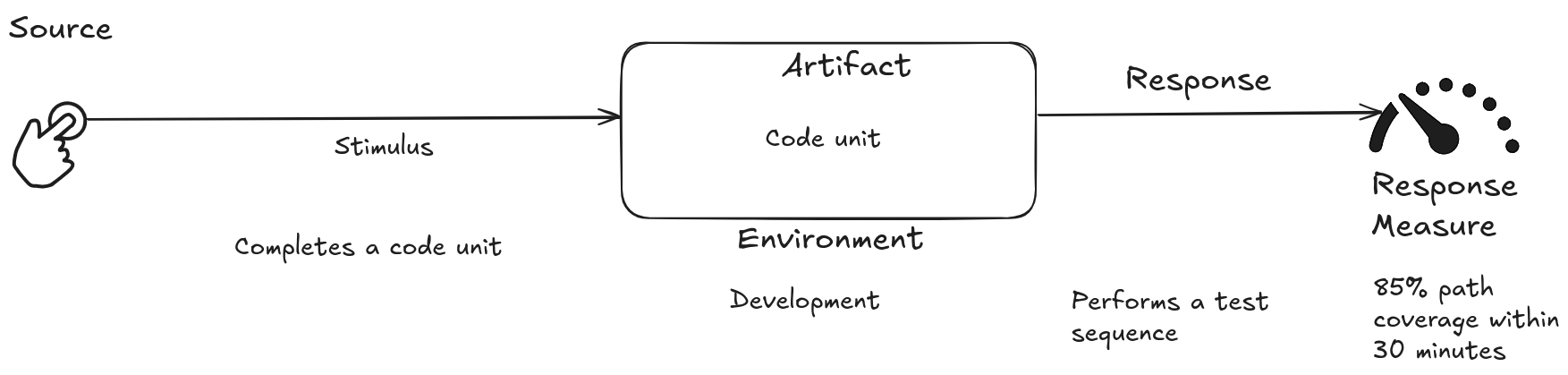

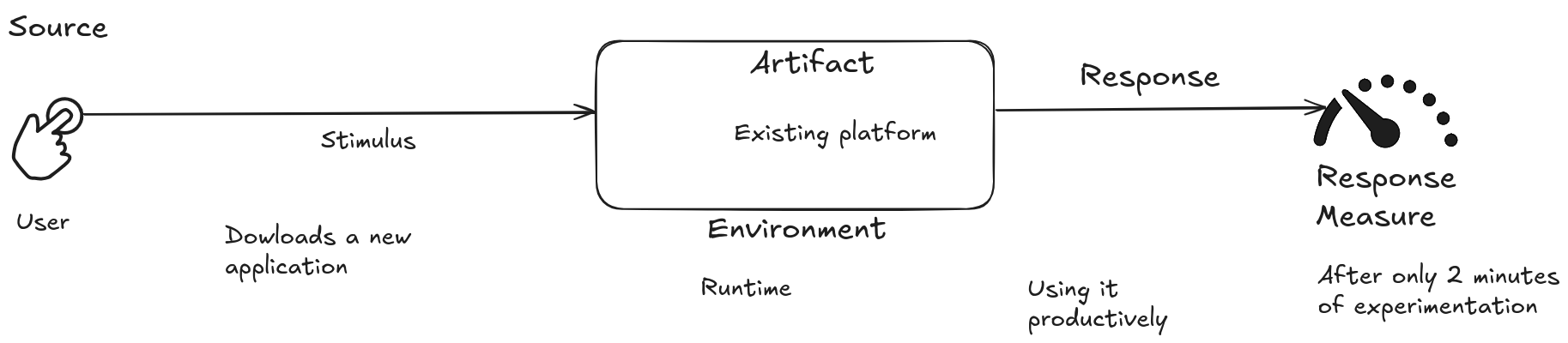

The following diagram illustrates the general scenario of quality attributes:

Demystifying Abstraction:

Imagine a security requirement that simply states: “The system must be secure.” What does this mean in practice? Secure against what types of threats? Under what conditions? A quality attribute scenario answers these questions, making the requirement testable and useful for the development team.

Structure of a Quality Attribute Scenario:

Sources commonly use a standard format, consisting of six parts, to specify all quality attribute requirements as scenarios. This common format addresses vocabulary issues, ensuring testability and clarity, and is not sensitive to arbitrary categorizations. The six parts of a quality attribute scenario are:

Stimulus Source: Who or what originates the stimulus? It could be a user, another system, a hardware device, or even the system itself.

Stimulus: The event that occurs in the system or project. It could be a user request, a hardware failure, an unauthorized access attempt, or any other event relevant to the quality attribute in question.

Environment: The context in which the stimulus occurs. It could be the system under full load, in maintenance mode, or in a specific hardware or software environment.

Artifact: The part of the system that is stimulated. It could be a software component, a database, a network interface, or any other system element.

Response: The expected behavior of the artifact in response to the stimulus. It could be the execution of a specific function, the generation of an event log, the sending of an alert, or any other observable action.

Response Measure: How the response is measured and evaluated. It could be response time, error rate, granted access level, or any other quantifiable metric that allows determining whether the requirement has been met.

Although it is common to omit one or more parts of the scenario, especially in the early stages of defining quality attributes, being aware of all parts encourages the architect to consider the relevance of each. This process leads to a more complete understanding of quality requirements and, consequently, a more robust and effective system.

By using quality attribute scenarios, the development team can ensure that the system not only functions as expected but also meets the stakeholders’ needs in terms of performance, security, usability, and other attributes raised during the architectural process.

So far, we have understood how the architectural synthesis process works, resulting in a valid and implementable architecture.

We also understand the importance of non-functional requirements as a means to realize functional requirements, and we have seen that these non-functional requirements have behaviors, with sources, stimuli, environments, etc.

We have a solid foundation so far, knowing what the needs are and what to do, using a systematic approach.

Now is the time to learn ways to materialize these quality attributes in the real world, and for that, there is also a process, or rather, a tactic.

Achieving Quality Attributes through Architectural Patterns and Tactics

A tactic is a design decision that influences the achievement of a quality attribute response and directly affects the system’s response to a given stimulus. Tactics can provide portability to one design, high performance to another, and integrability to a third.

Availability in Software Architecture

Availability describes a system’s ability to be ready to perform its functions when needed. This means that, in addition to functioning correctly, the system must also recover from failures.

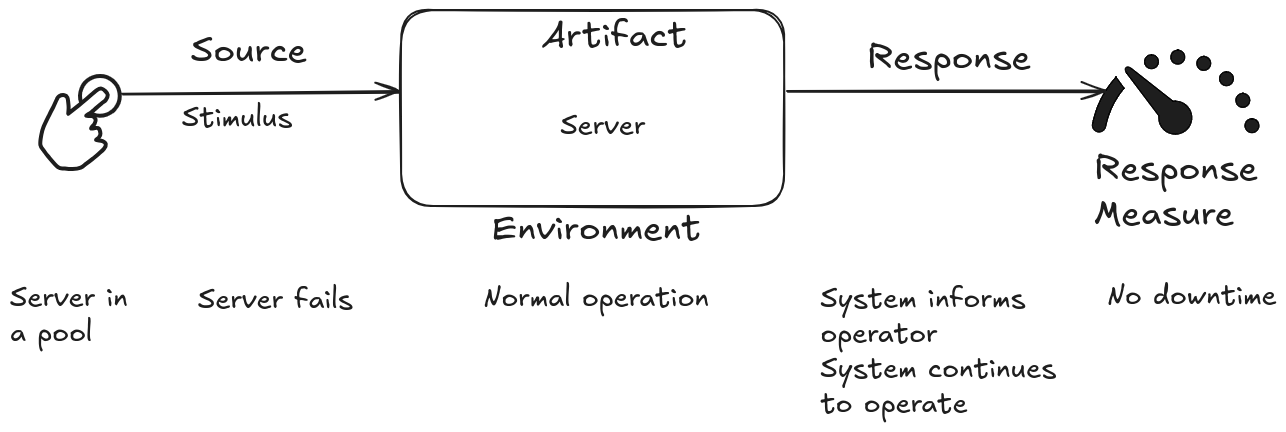

Scenario for Availability

Availability means ensuring that the software is ready to perform its functions when required. This broad concept encompasses both the reliability and the recovery capability of the system.

A scenario for availability describes how the system should behave in the event of a failure, considering:

Source of Stimulus: Origin of the failure (internal or external, such as hardware, software, environment).

Stimulus: Type of failure (e.g., omission, collision, incorrect timing).

Environment: Conditions under which the failure occurs (e.g., during normal operation, initialization).

Artifact: Part of the system affected by the failure.

Response: System action in response to the failure (e.g., normal operation, repair mode).

Measure of Response: Metrics to evaluate the success of the response (e.g., recovery time).

Use Case

A server in a server farm fails during normal operation, and the system notifies the operator and continues to operate with no downtime.

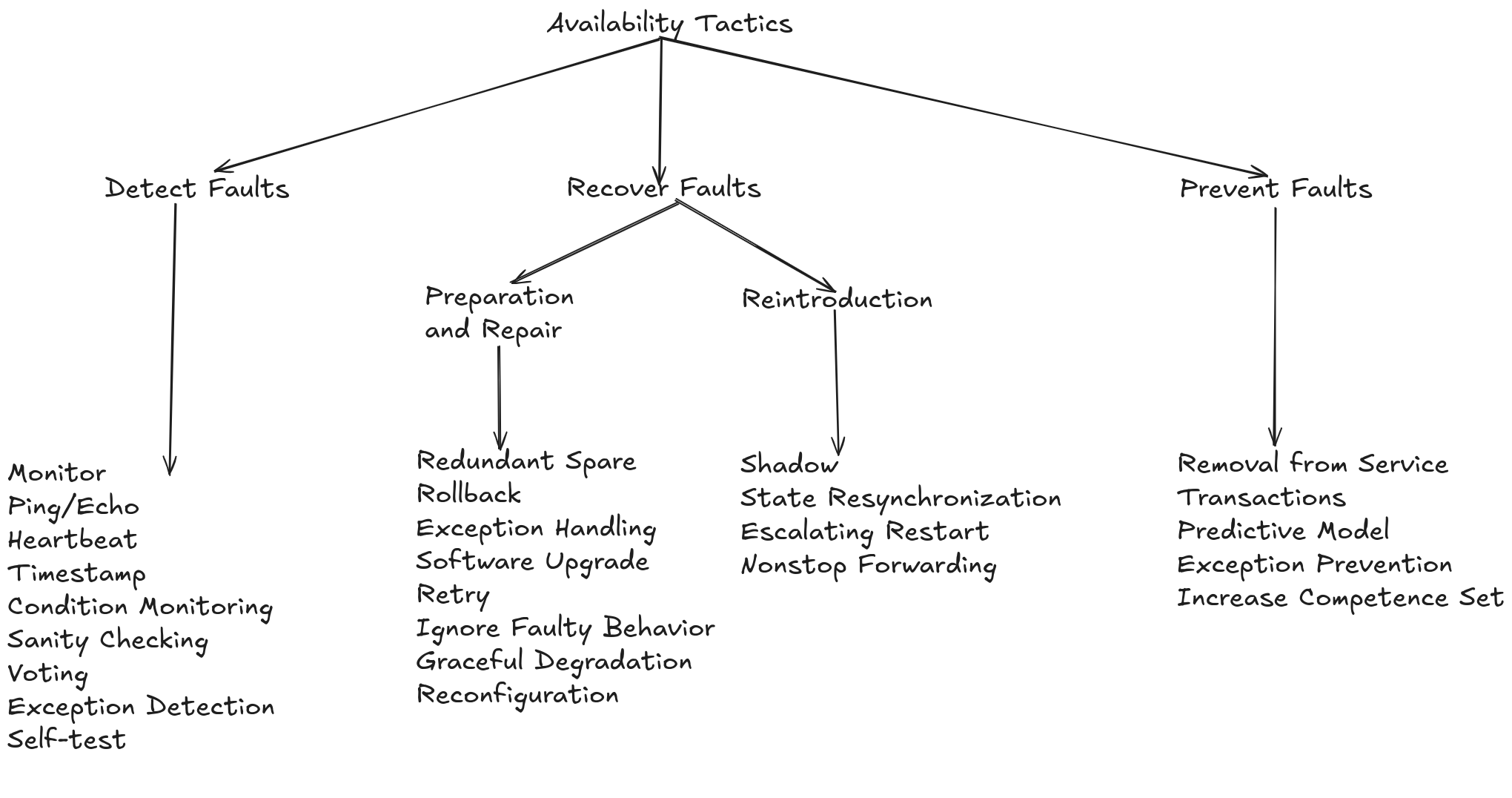

Tactics for Availability

Availability tactics aim to prevent and mitigate the impact of failures, including:

Failure Prevention

Eliminating Single Points of Failure: Implement redundancy to prevent the failure of a single component from causing system unavailability.

Fault Tolerance: Allow the system to continue operating in a degraded state, even if some components fail.

Failure Detection

Monitoring: Continuously check the state of system components to quickly detect failures.

Ping/Echo Detection: Send periodic signals to components and check responses to detect communication failures.

Exception Checking: Detect abnormal conditions during code execution.

Failure Recovery

Repair: Correct the cause of the failure and restore the system to its operational state.

Reintroduction: Safely reintroduce a repaired component into the system.

Redundancy: Use redundant components to replace those that have failed.

Availability Patterns

Availability patterns are reusable solutions for common design problems related to availability. Like:

Substitute: Designate a component to take over the responsibilities of a failed component, ensuring the continuity of operation.

Scaling: Dynamically adjust system resources in response to changes in demand, maintaining performance and availability.

Examples of Technologies, Tools, or Services for Availability

Various technologies and services, both cloud-based and on-premises, as well as open-source, can be used to implement availability patterns:

Data Redundancy: Databases like Apache Cassandra offer data replication, distributing copies of data across multiple nodes to ensure availability even if one node fails.

Load Balancing: Tools such as HAProxy and NGINX distribute network traffic across multiple servers, preventing overload and increasing availability.

Virtualization: Virtualization platforms like VMware vSphere and Xen allow the creation of virtual machines (VMs) that can be easily moved and replicated, facilitating redundancy and failure recovery.

Deployability in Software Architecture

Deployability refers to the ability of software to be deployed, i.e., allocated to an environment for execution within predictable and acceptable time and effort.

Additionally, if the new deployment does not meet its specifications, it should be reversible, again within predictable and acceptable time and effort.

Scenario for Deployability

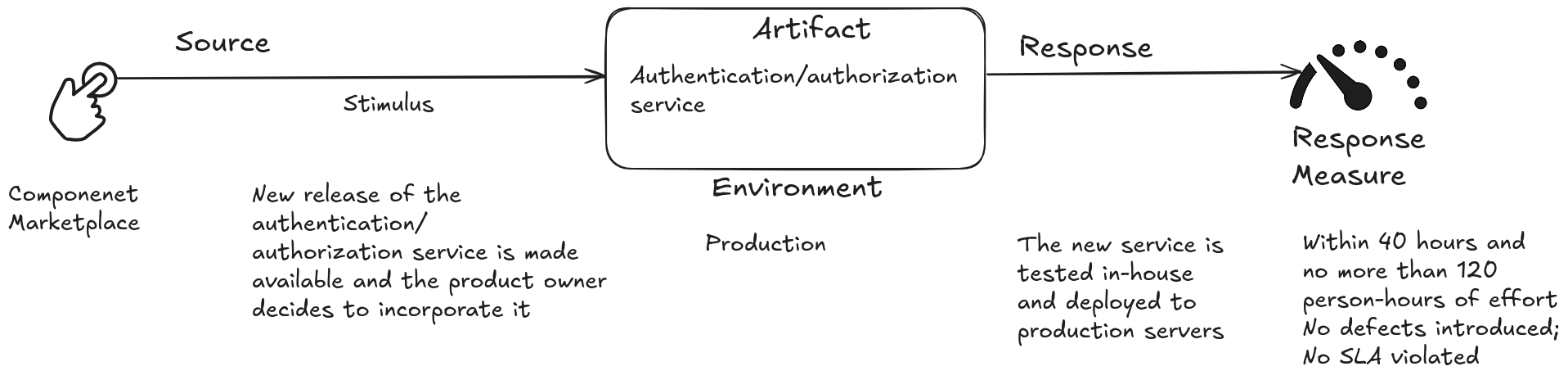

A typical deployability scenario might be described as follows:

Source of Stimulus: A new version of the software is made available.

Stimulus: The new version needs to be deployed to a production environment.

Environment: The production environment may be local, cloud-based, or hybrid.

Artifact: The new version of the software, including code, configurations, and dependencies.

Response: The software is successfully deployed in the production environment.

Response Measure: Time and effort required to deploy the software, number of errors or issues encountered during deployment, time and effort needed to roll back the deployment if it fails.

Use Case:

A new version of an authentication/authorization service (which our product uses) is released in the component marketplace, and the product owner decides to incorporate this version into the product. The new service is tested and deployed in the production environment within 40 elapsed hours and no more than 120 man-hours of effort. The deployment is defect-free and no SLA (Service Level Agreement) is violated.

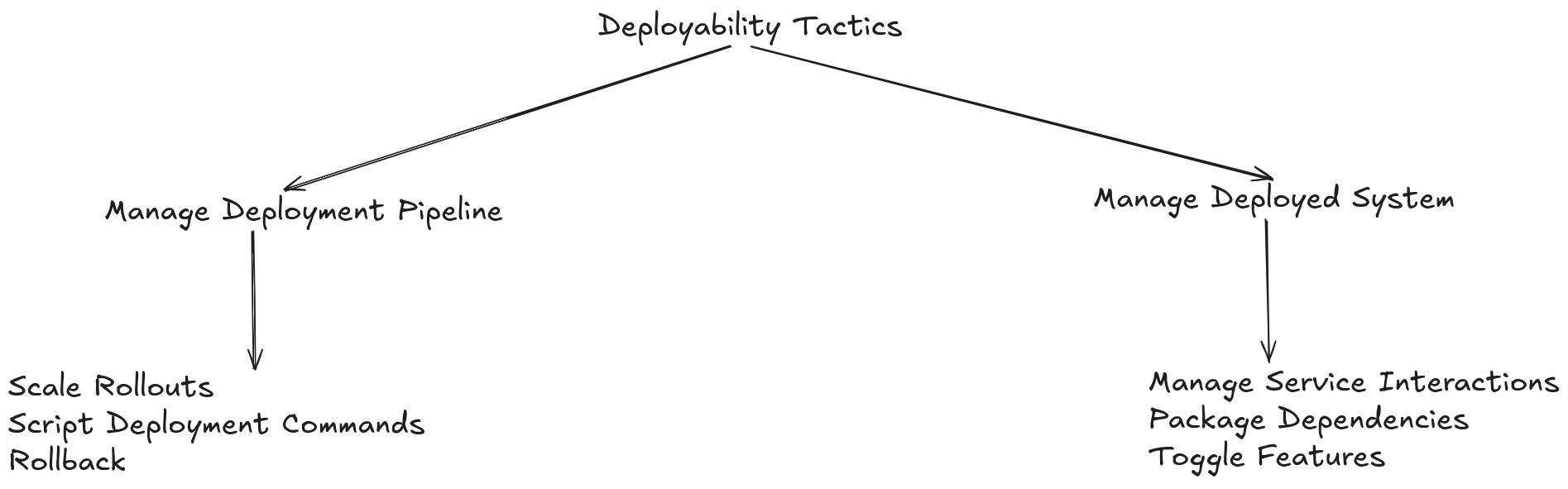

Tactics for Deployability

The tactics for deployability aim to ensure that new software or hardware components are deployed within acceptable constraints of time, cost, and quality.

The deployment pipeline management tactics focus on how software is moved from development to production.

The deployment system management tactics focus on how to manage a system both during its deployment and after it has been deployed.

Minimize Dependencies: Reducing dependencies between system components simplifies the deployment process and lowers the risk of compatibility issues.

Manage Components: Use a component management system to track different versions and dependencies of system components.

Automate Deployment: Automate the deployment process to reduce time and effort and minimize the risk of human errors.

Use Testing Environments: Deploy and test the software in test environments that mirror the production environment to identify and address issues before production deployment.

Deploy in Phases: Break the deployment into smaller, manageable phases to reduce risk and allow for more frequent testing and validation.

Monitor Deployment: Monitor the deployment process and production environment to quickly detect and address issues.

Rollback: Implement a rollback mechanism to quickly revert to the previous version of the software in case of problems.

Deployability Patterns

Several architectural patterns can be used to enhance deployability:

Containers: Enable the creation of self-contained software packages, including all necessary dependencies, which simplifies deployment across different environments.

Microservices: Decomposes a system into independent and autonomous services that can be deployed and scaled independently, increasing flexibility and deployment speed.

Blue/Green Deployment: Involves creating two identical instances of the production environment, one “blue” (currently running) and one “green” (new version). The new version is deployed in the “green” environment, tested, and then traffic is redirected to it.

Canary Releases: The new version is gradually deployed to a small group of users before being released to everyone.

Rolling Updates: The update is performed gradually, replacing old instances with new ones one at a time.

Practical Examples of Technologies, Tools, or Services for Deployability

Various technologies, tools, and services can be used to implement deployability patterns and tactics. Here are some examples:

Docker: An open-source platform for creating and managing software containers.

Kubernetes: An open-source platform for automating the deployment, scaling, and management of containerized applications.

Jenkins: An open-source continuous integration and continuous delivery (CI/CD) tool for automating the build, test, and deployment process of software.

Terraform: An Infrastructure as Code (IaC) tool that allows for the definition of infrastructure using configuration files.

Ansible: An automation tool that can be used to automate deployment, configuration, and management of systems.

Energy Efficiency in Software Architecture

The growing concern about energy efficiency in computing systems requires software architects to consider energy consumption as a primary quality attribute.

Scenario for Energy Efficiency

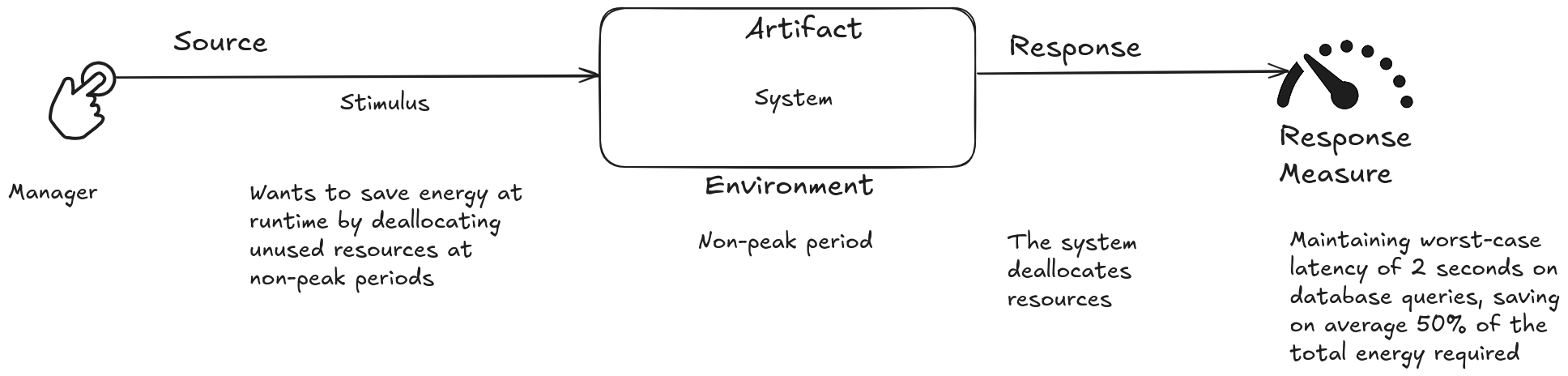

The need for energy efficiency arises when there is a desire to conserve or manage energy consumption without compromising system functionality. A typical scenario might involve:

Source of Stimulus: A data center manager concerned with energy costs.

Stimulus: The desire to reduce energy consumption during periods of low demand.

Environment: A cluster of servers in a data center.

Artifact: The data center’s energy management system.

Response: The system deactivates or puts idle servers into a low-power mode during periods of low demand.

Measure of Response: Reduction in the total energy consumption of the data center, measured in kWh.

Use Case:

A manager aims to save energy during runtime by deallocating unused resources during off-peak periods. The system deallocates resources while maintaining a worst-case latency of 2 seconds for database queries, achieving an average energy savings of 50% of the total required energy.

Tactics for Energy Efficiency

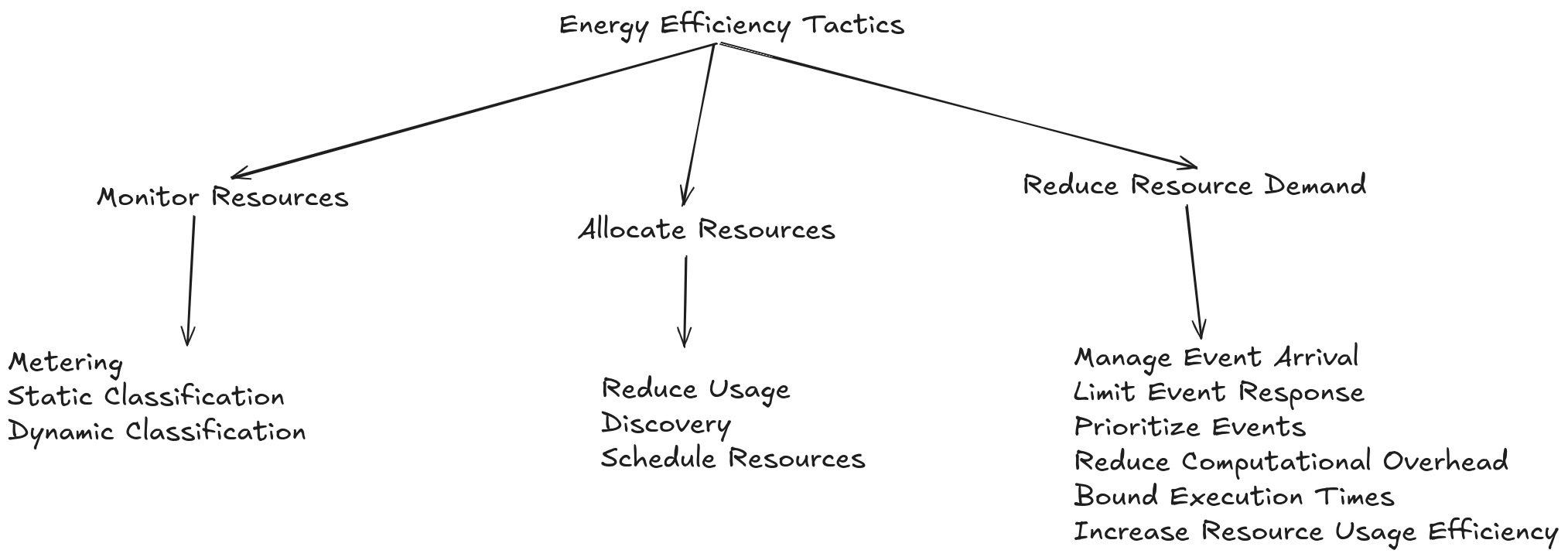

Monitor Resources: You cannot manage what you cannot measure, so energy efficiency tactics start with monitoring resources.

Allocate Resources: Resource allocation means assigning resources to work in a way that is mindful of energy consumption.

Reduce Resource Demand Manage the arrival and response to events, prioritize events by leaving some low-priority ones unaddressed, reduce computational overhead, limit execution times, and optimize resource usage efficiency, with the common goal of doing less work and thus saving energy.

Resource Management: Monitoring and controlling the use of resources like CPU, memory, disk, and network.

Reducing Resource Demand: Optimizing algorithms and data structures to minimize resource usage.

Adjusting Performance: Finding a balance between performance and energy consumption.

Using Efficient Hardware: Choosing hardware with better energy efficiency.

Turning Off Inactive Resources: Deactivating components or subsystems that are not in use.

Energy Efficiency Patterns

Design patterns provide repeatable solutions to common problems in software design:

Green Computing: Designing systems with a focus on minimizing energy consumption during operation.

Virtualization: Using virtual machines to consolidate servers and improve resource utilization.

Thin Provisioning: Allocating storage resources dynamically and as needed.

Practical Examples of Technologies, Tools, or Services for Energy Efficiency

Several technologies, tools, and services can be used to implement the energy efficiency tactics mentioned:

AWS Lambda: Allows you to run code without provisioning or managing servers, paying only for the compute time used, which can contribute to energy efficiency.

Google Cloud Run: Similar to AWS Lambda, it runs managed containers in a scalable manner with pay-as-you-go billing.

Kubernetes with Cluster Autoscaler: Container orchestration that automatically adjusts the number of pods based on workload, saving energy.

Prometheus: A monitoring platform that can be used to track energy consumption metrics.

Virtualization: Allows multiple applications to be consolidated on a single physical server, optimizing hardware usage.

Energy Management Tools: Software that enables configuring energy-saving policies on servers and desktops.

Integrability in Software Architecture

Integrability goes beyond simply making separate software components work together; it encompasses the costs, technical risks, and implications of integrating components both now and in the future.

Scenario for Integrability

Imagine a supply chain management system that needs to integrate data from multiple suppliers, each with their own systems and data formats. Efficient and cost-effective integration is crucial for the success of the system, allowing for unified views, process automation, and optimized decision-making.

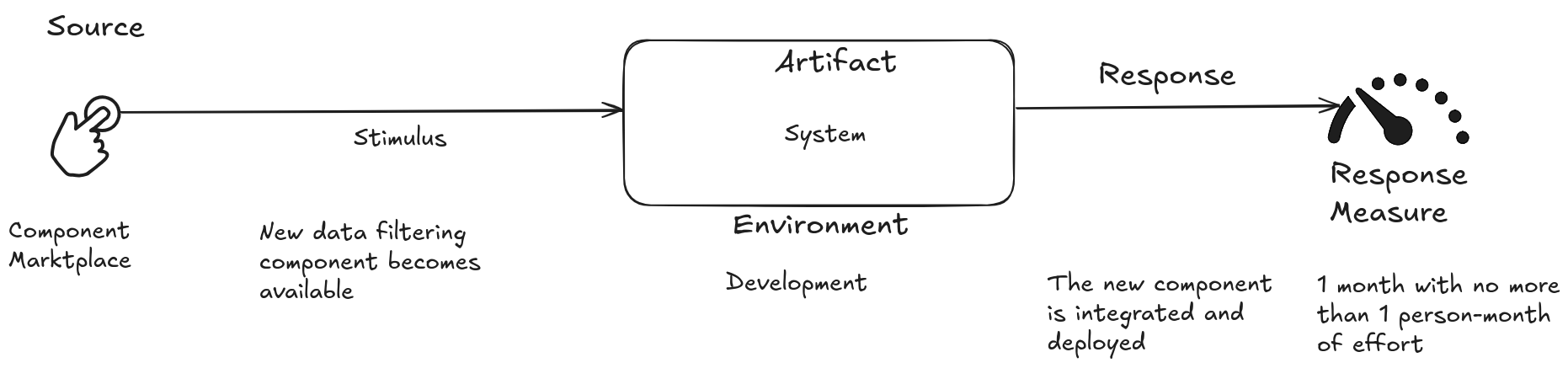

A typical scenario looks like:

Stimulus Source: A growing e-commerce company needs to integrate its electronic invoicing (NF-e) system with its backoffice system to automate order processing and improve efficiency.

Stimulus: The need to integrate the NF-e system with the backoffice system to automate the workflow.

Environment: The company’s IT infrastructure, where the NF-e system and the backoffice system operate.

Artifact: The company’s integrated management system, combining the NF-e and backoffice systems.

Response: The NF-e system is integrated with the backoffice system using a messaging service. This service acts as an intermediary, allowing the two systems to share data asynchronously and reliably.

Response Measure: Time required to integrate the systems, integration cost, and reduction in manual errors in order processing.

Use Case

A new data filtering component has become available on the component market. The new component is integrated into the system and deployed within 1 month, with a maximum of 1 person-month of effort.

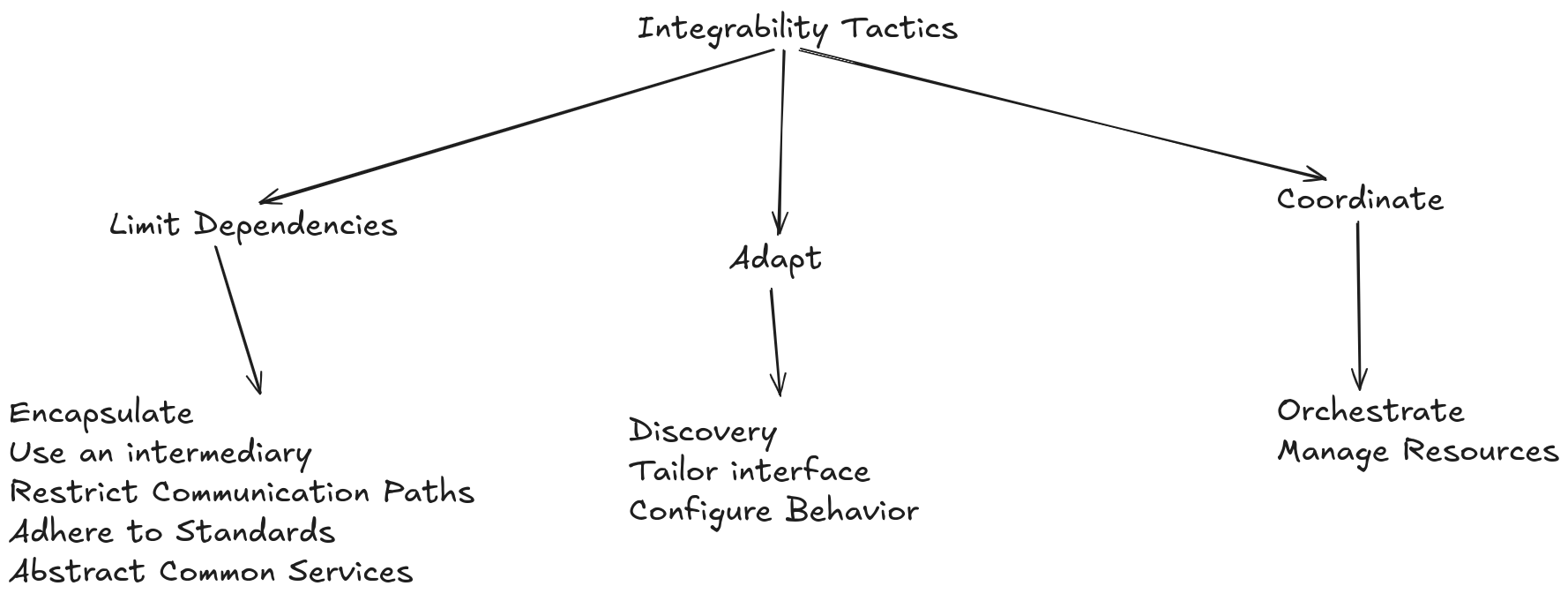

Tactics for Integrability

The tactics for integrability aim to minimize the challenges of connecting different software components.

Limit Dependencies

Aim to reduce the number of dependencies between a component being integrated (C) and the system into which it is being integrated (S).

Adapt

Deal with resolving differences between C and S. There are three tactics in this category:

Coordinate

Aim to integrate components that were not designed to work together or may not be aware of each other’s existence.

Minimize Dependencies: Limit dependencies between components to reduce the impact of changes and promote reuse.

Abstract Interactions: Define clear and concise interfaces to facilitate communication between components, hiding implementation details.

Manage Data: Implement efficient mechanisms for data translation, transformation, and synchronization between components.

Orchestrate Interactions: Establish clear workflows and control mechanisms to ensure effective communication and collaboration between components.

Integrability Patterns

Various architectural patterns can facilitate integrability, such as:

Microservices: Decompose the system into independent, loosely coupled services with well-defined responsibilities, simplifying integration and management.

Message Queues: Enable asynchronous and reliable communication between components, decoupling them and increasing system scalability.

APIs (Application Programming Interfaces): Provide standardized interfaces for interacting with components, facilitating integration and the consumption of functionalities.

API Gateways: Consolidate and manage multiple APIs, simplifying integration with external systems.

Examples of Technologies, Tools, or Services for Integrability

Tools and services that implement these patterns:

Apache Kafka: An open-source event streaming platform that implements the Message Queues pattern, ideal for integrating microservices and building scalable distributed systems.

Kong Gateway: An open-source API gateway that offers routing, transformation, and API management, simplifying integration with external systems and applying security policies.

MuleSoft Anypoint Platform: An Integration Platform as a Service (iPaaS) that provides tools to connect applications, data, and devices in the cloud or on-premises, using various integration patterns.

Modifiability in Software Architecture

Modifiability refers to how easily a software system can be altered throughout its lifecycle, accommodating new features, fixing defects, and adapting to new requirements and environments.

Scenario for Modifiability

An e-commerce system that is constantly evolving needs to adapt to market demands, such as new payment methods, integrations with marketplaces, and customized features for users. The system’s architecture should support rapid implementation of these changes without compromising the platform’s stability and performance.

Scenario:

Stimulus Source: A logistics company seeking to optimize the operations of its vehicle fleet.

Stimulus: The need to adapt the vehicle tracking system to incorporate new types of sensors and actuators, keeping up with technological advancements and demands for more complex information, such as real-time fuel consumption and refrigerated cargo temperature.

Environment: The vehicle tracking system operates across a variety of mobile devices (vehicles) with different processing capabilities, unstable network connectivity, and varying power consumption requirements.

Artifact: The software system embedded in the mobile devices of the vehicle fleet, responsible for collecting, processing, and transmitting sensor data, as well as receiving and executing actuator commands.

Response: The architecture of the tracking system is modified to use a message bus that abstracts communication with sensors and actuators. This abstraction allows new types of sensors and actuators to be added to the system without the need to modify the core application code.

Response Measure:

- Time required to integrate a new type of sensor or actuator: A significant reduction in integration time is expected.

- Cost of adding new types of sensors and actuators: The cost should be lower due to the reuse of the core application code.

- Impact on system performance and energy consumption: Performance and energy consumption should not be significantly impacted by the addition of new sensors and actuators.

Use Case

A developer wants to change the user interface. This change will be made in the code during design time, will take less than three hours to implement and test, and will have no side effects.

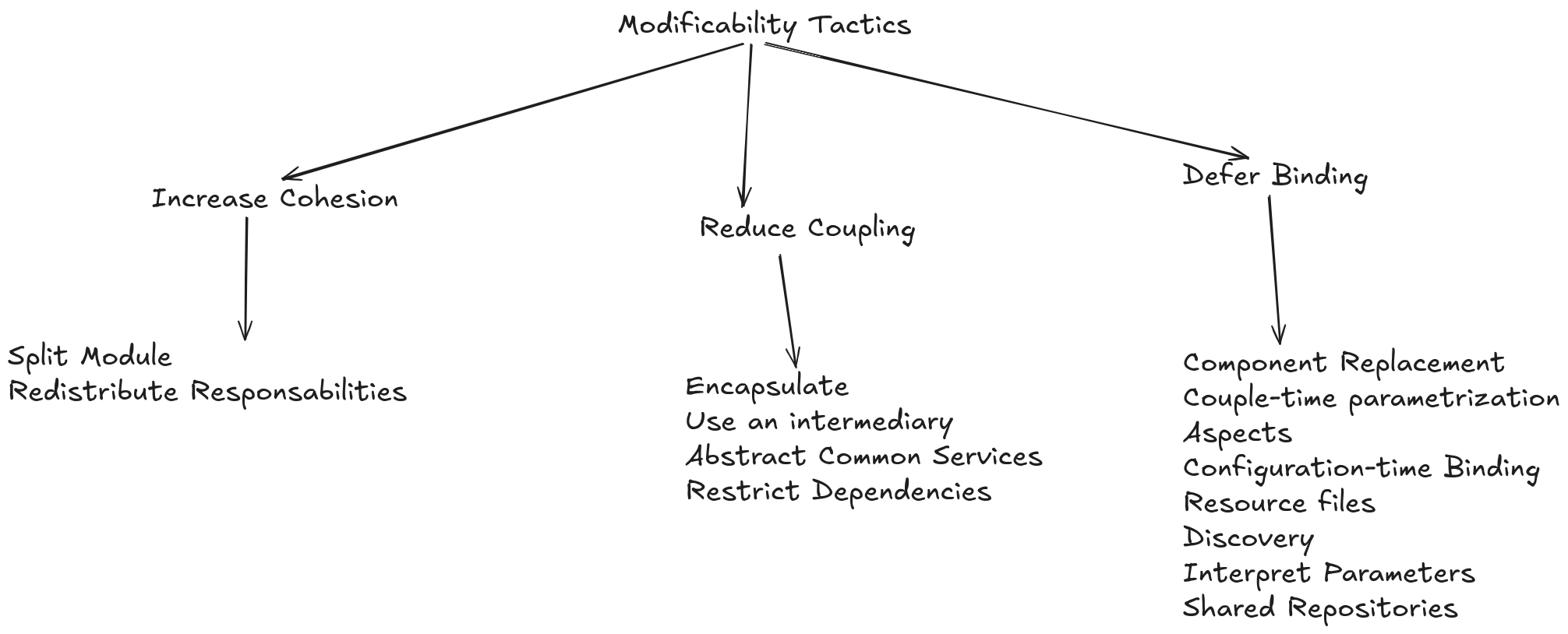

Tactics for Modifiability

Modifiability tactics aim to facilitate changes to a system, minimizing associated costs and risks:

Reduce Coupling: Limit dependencies between modules so that modifications in one module have minimal impact on others.

Defer Binding: Allow decisions about specific implementations to be made as late as possible in the development lifecycle, using mechanisms like plugins and external configurations.

Abstract Common Services: Identify common functionalities and encapsulate them in reusable modules to avoid code duplication and simplify maintenance.

Encapsulate Variable Parts: Isolate aspects of the system that are likely to change, such as domain-specific algorithms or integrations with external systems, into modules with well-defined interfaces.

Modifiability Patterns

Various architectural patterns can enhance a system’s modifiability:

Microservices: Decompose the system into independent, loosely coupled services, allowing them to be modified and deployed individually without affecting other services.

Dependency Injection: Allow dependencies between modules to be provided externally, facilitating component replacement and testing.

Aspect-Oriented Programming (AOP): Separate cross-cutting concerns, such as logging and security, from the main code, making the system more modular and easier to modify.

Practical Examples of Technologies, Tools, or Services for Modifiability

Kubernetes: An open-source container orchestration platform that facilitates the deployment, management, and scaling of microservices-based applications, making updates and modifications more efficient.

Spring Framework: A Java framework that provides support for dependency injection and AOP, making applications more modular, testable, and easier to modify.

Performance in Software Architecture

Performance, critical for user satisfaction and system success, refers to a system’s ability to meet response time demands within a given workload limit.

Performance Scenario

A typical performance scenario might involve:

Source of Stimulus: Hardware failure, traffic peak

Stimulus: Loss of server connection, drastic increase in requests

Artifact: The system as a whole, specific component

Environment: Production, testing environment

Response: Continued operation in degraded mode, automatic recovery

Measure of Response: Recovery time, number of lost transactions

Use Case

Five hundred users initiate 2,000 requests within a 30-second interval during normal operations. The system processes all requests with an average latency of two seconds.

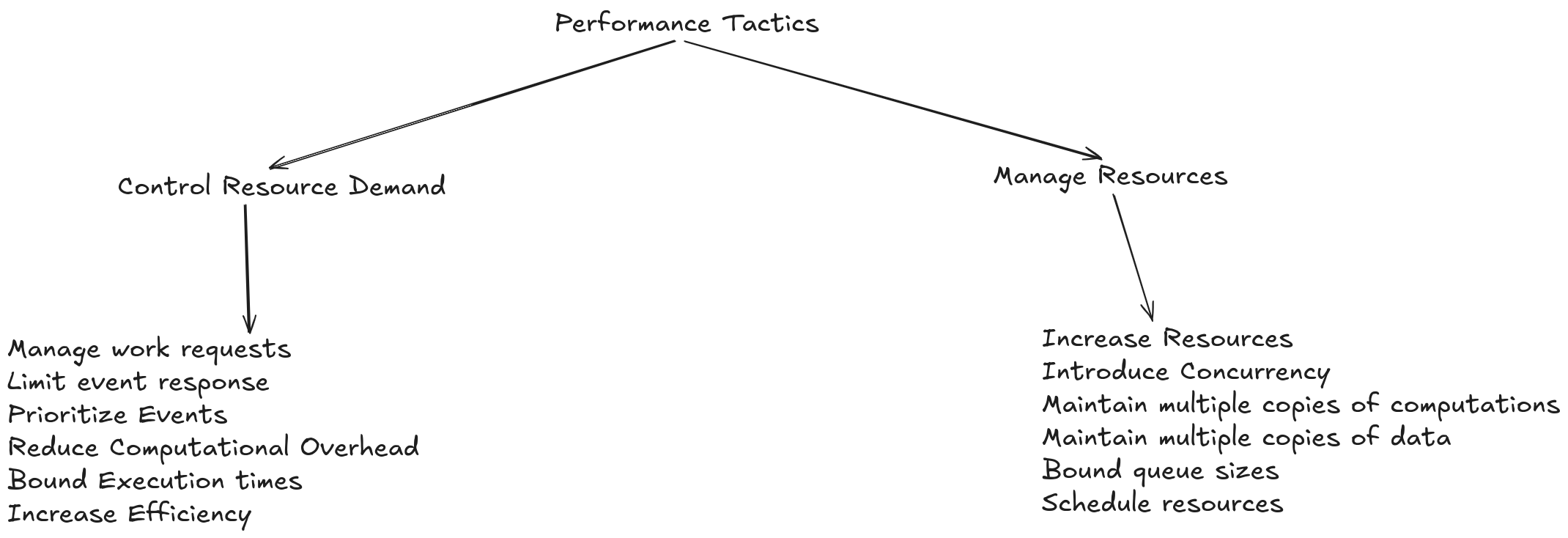

Tactics for Performance

Performance tactics are design strategies used to ensure that a system can respond quickly and handle large volumes of data, such as:

Manage Resources: Even if the demand for resources cannot be controlled, the management of these resources can be. Sometimes, one resource can be substituted for another. For example, intermediate data can be kept in a cache or regenerated depending on which resources are most critical: time, space, or network bandwidth.

Manage Contended Resources: Limit the use of shared resources like databases and queues to minimize wait times and bottlenecks.

Use Resources Effectively: Reduce resource consumption through techniques such as caching, optimized algorithms, and data compression.

Control Resource Demand: Prioritize critical tasks, limit queues, and use throttling mechanisms to prevent system overload.

Keep Concurrency Under Control: Limit the number of concurrent threads and processes to reduce context-switching overhead and resource contention.

Performance Patterns

Various architectural patterns that can enhance performance include:

Divide and Conquer: Break the system into smaller, independent components for parallel processing, reducing overall execution time.

Cache: Store frequently accessed data in caches to reduce access to slower resources, such as databases and external services.

Resource Pools: Maintain a set of pre-initialized resources to avoid the overhead of frequent creation and disposal, such as database connections.

Practical Examples of Technologies, Tools, or Services for Performance

Amazon ElastiCache: A managed caching service that can be used to improve the performance of web applications by storing frequently accessed data in memory. It supports various caching engines like Redis and Memcached and integrates with other AWS services.

Spring Boot: A Java framework that facilitates the creation of lightweight, independent microservices. It offers features such as auto-configuration, embedded monitoring, and support for different communication formats like REST and asynchronous messaging.

Apache Kafka: A distributed streaming platform that allows for the construction of real-time data pipelines and streaming applications. It provides high processing capacity and fault tolerance, making it suitable for handling large volumes of data.

Considerations on the Attributes of Safety and Security

The quality attributes of safety and security are both critical in software systems, but they address different aspects of system protection and operation. Here’s a look at the differences between these two attributes:

Safety

Definition: Safety refers to a system’s ability to operate without causing harm to people, the environment, or other systems, even in the presence of faults or errors. The focus is on preventing accidents and controlling risks.

Security

Definition: Security refers to a system’s ability to protect data and operations from unauthorized access, malicious attacks, and other threats that could compromise the integrity, confidentiality, and availability of information.

Safety in Software Architecture

In software engineering, safety refers to a system’s ability to operate without causing harm to people or the environment. The importance of safety in computer-controlled systems has grown exponentially as these systems become increasingly integrated into our lives, from autonomous vehicles to medical devices and industrial control systems.

Failures in these systems can have catastrophic consequences, making safety a critical quality to consider from the early stages of software architecture design.

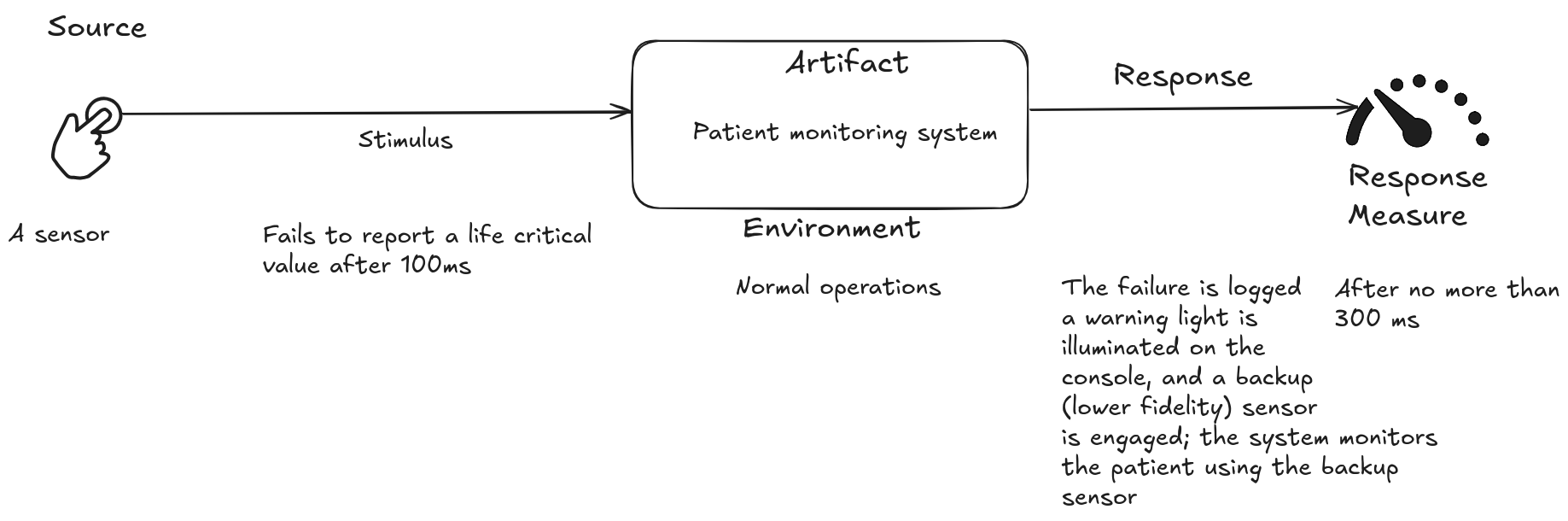

Safety Scenario

A safety scenario describes a situation where system safety is critical. An examples:

Source of Stimulus: What triggers the risk situation? (e.g., hardware failure, software error, user action)

Stimulus: What is the nature of the event? (e.g., sensor sends invalid data, software tries to access unallocated memory, user presses the wrong button)

Artifact: Which part of the system is affected? (e.g., control module, user interface, database)

Response: How should the system react to the stimulus? (e.g., safely shut down the system, alert the user, log the event)

Measure of Response: How is the effectiveness of the response measured? (e.g., time to shut down, false positive rate of alerts, completeness of the log)

Use Case

An example of a security scenario is: A sensor in the patient monitoring system does not report a critical life value within 100 ms. The failure is logged, a warning light is activated on the console, and a backup (low-fidelity) sensor is triggered. The system monitors the patient using the backup sensor within a maximum of 300 ms.

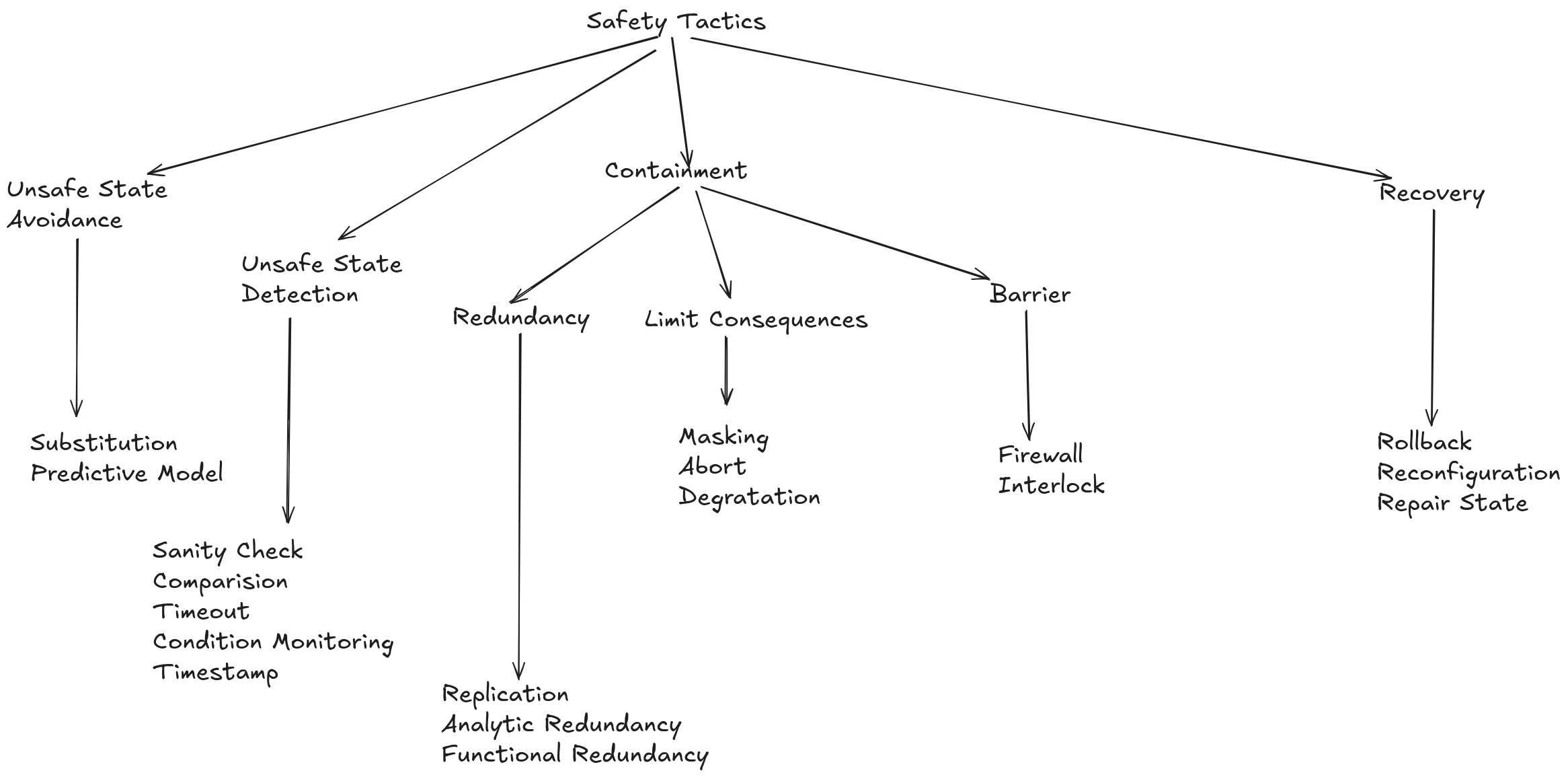

Tactics for Safety:

Preventing Unsafe States: Focuses on preventing the system from entering a potentially dangerous state.

Detecting Unsafe States: Even with preventive measures, early detection of unsafe states is crucial.

Containment: Containment tactics limit the impact of failures by preventing their spread and allowing the system to continue operating, possibly with reduced functionality.

Recovery: After detecting and containing an unsafe state, recovery tactics restore the system to a stable and consistent operational state.

Prevention of Unsafe States:

Substitution: Replaces software components prone to failure with more robust hardware alternatives, such as watchdogs and interlocks. Maintain Safe State: Implements mechanisms to ensure the system remains in a safe state even in case of failures, such as hardware and software redundancy, fault tolerance mechanisms, and rigorous data validation.

Detection of Unsafe States:

Fault Detection: Continuously monitors the system to identify and signal faults, using techniques like code checks, heartbeat monitoring, and deadlock detection mechanisms.

Containment and Recovery:

Fault Containment: Isolates faults to prevent them from spreading throughout the system, using techniques like firewalls, sandboxes, and compartmentalization.

Fault Recovery: Implements mechanisms to restore the system to a safe operational state after a fault, such as transaction rollbacks, fallback mechanisms, and system rebooting.

Safety Patterns

Safety patterns are reusable and proven design solutions for achieving safety in various contexts. One such pattern is “Separate Safety,” which involves dividing the system into safety-critical and non-safety-critical parts.

Advantages:

Simplified Certification: Allows certification of only the safety-critical parts, reducing costs and time.

Fault Isolation: Reduces the risk of failures in non-critical components affecting the overall safety of the system.

Practical Examples of Technologies, Tools, or Services for Safety

AWS IoT Greengrass: Enables deploying and running code locally on IoT devices, including security features such as device authentication and data encryption.

Robot Operating System (ROS): A flexible framework for writing robotics software, including tools and libraries for developing secure robotic systems.

Ardupilot: An open-source system for unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs), which includes safety features such as geofencing and onboard safety modes.

Programmable Logic Controllers (PLCs) with Redundancy: Used in industrial automation, these controllers can be configured in redundant pairs to ensure safety in case of failure of one of the controllers.

Security in Software Architecture

Security in a software system measures the ability to protect data and information from unauthorized access while ensuring access for authorized people and systems. This characteristic is crucial for the system’s reliability and for maintaining user trust.

Security can be characterized by three main aspects: confidentiality, integrity, and availability (CIA):

Confidentiality: Ensures that data and services are protected from unauthorized access.

Integrity: Ensures that data and services are not subject to unauthorized manipulation.

Availability: Ensures that the system is available for legitimate use.

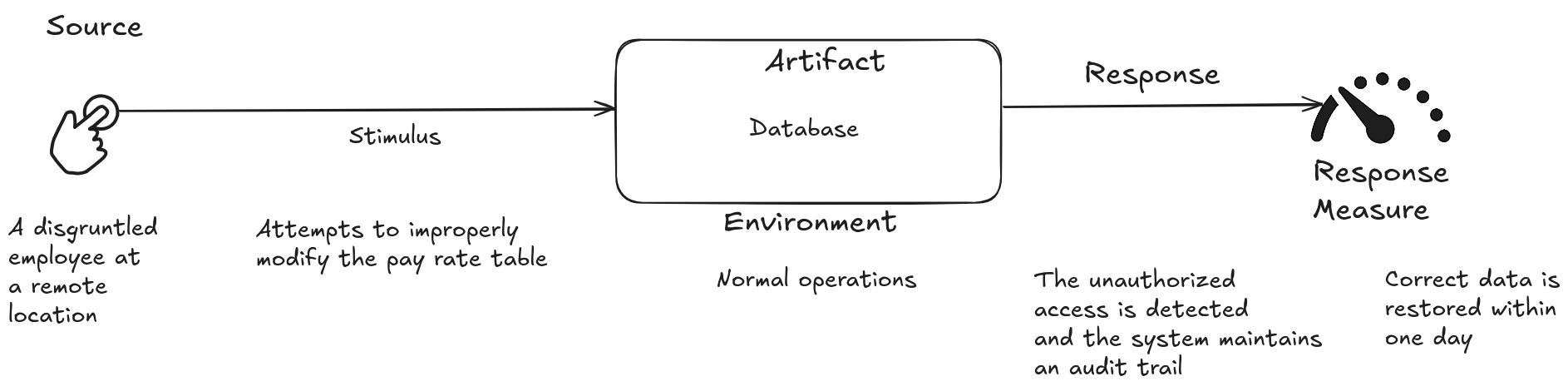

Scenarios for Security

Security Scenarios

Security scenarios are used to describe situations and system responses to potential threats. They help identify and analyze potential security risks. A security scenario typically includes:

Source of Stimulus: The origin of the threat, such as a hacker or a malicious internal user.

Stimulus: The action representing the threat, such as an unauthorized access attempt or malicious code injection.

Environment: The context in which the threat occurs, such as the company’s network or a public web server.

Artifact: The component of the system targeted by the threat, such as a database or a web service.

Response: The action taken by the system to handle the threat, such as blocking unauthorized access or logging the attack attempt.

Response Measure: The metric used to evaluate the effectiveness of the response, such as the time required to detect and block the threat.

Use Case

An unhappy employee in a remote location attempts to improperly modify the salary rate table during normal operations. Unauthorized access is detected, the system maintains an audit trail, and correct data is restored within one day.

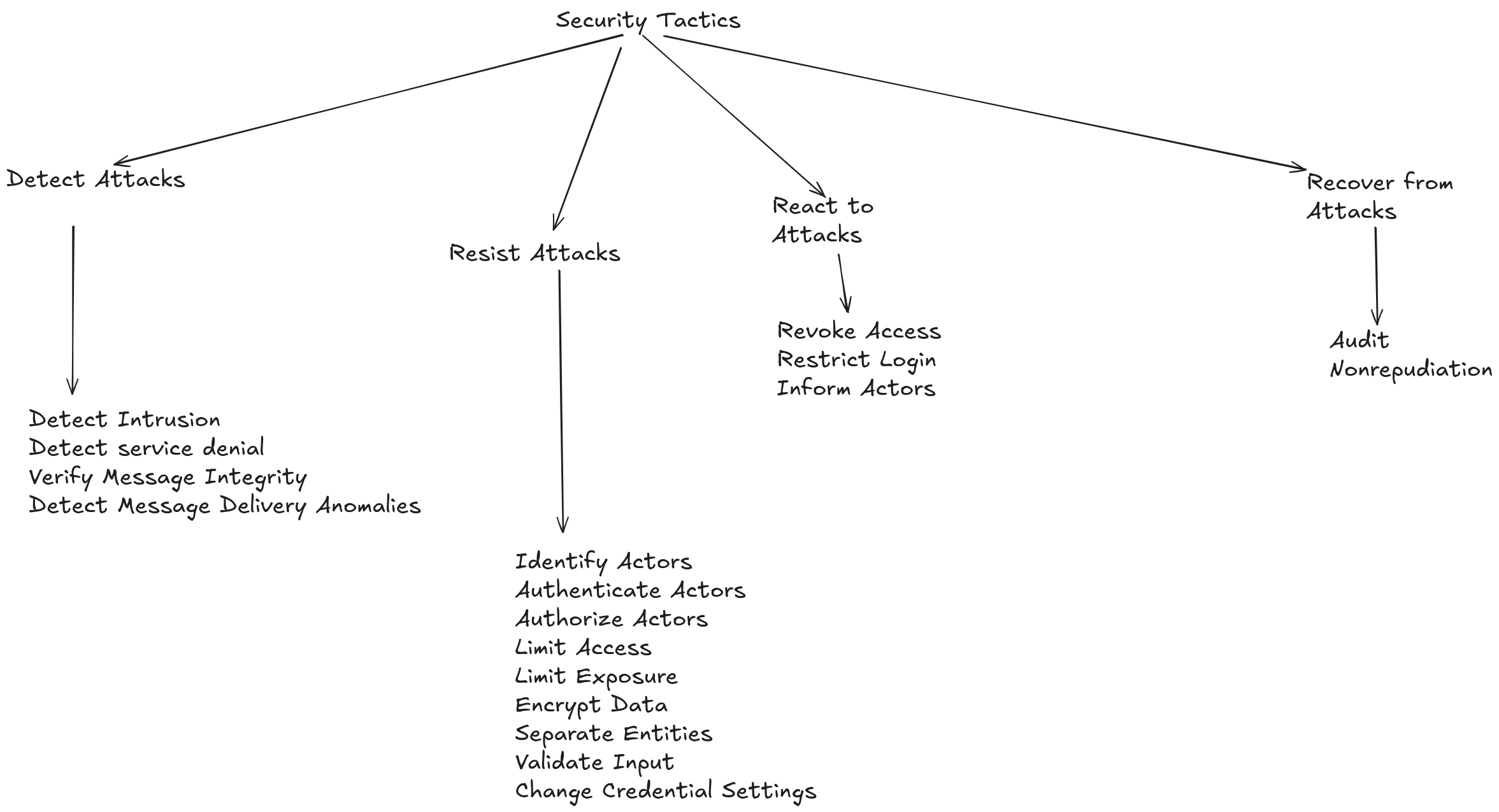

Tactics for Security

Security tactics are design decisions that directly influence the system’s ability to withstand attacks and maintain confidentiality, integrity, and availability (CIA).

Security tactics can be divided into four main categories: detection, resistance, reaction, and recovery.

Detecting Attacks: The first line of defense in mitigating security threats.

Resisting Attacks: The next line of defense is to withstand the attack and prevent it from exploiting system vulnerabilities.

Responding to Attacks: A timely and effective response is vital to mitigating the damage caused by an attack.

Recovering from Attacks: After a security incident, it is crucial to restore the system to a secure operational state and recover any lost or compromised data.

Detection

Detect Intrusion: Identify suspicious activities that may indicate an attack.

Detect Denial of Service: Monitor the system to identify and mitigate denial of service attacks.

Authenticate Actors: Verify the identity of users and systems attempting to access the system.

Authorize Actors: Verify if an authenticated user or system is permitted to perform a particular action.

Detect Anomalies in Message Delivery: Monitor communication between system components to detect suspicious or modified messages.

Resistance

Resist Brute Force Attacks: Use mechanisms like strong passwords and login attempt limits to deter brute force attacks.

Use Encryption: Protect confidential data at rest and in transit using encryption algorithms.

Minimize Attack Surface: Reduce the amount of code and system components exposed to potential attacks.

Separate Entities: Divide the system into isolated components to limit the impact of a potential attack.

Reaction

Block Access: Deny access to unauthorized users or systems.

Log Security Events: Record suspicious events for later analysis and to help identify and mitigate future threats.

Alert Administrators: Notify system administrators about potential attacks or suspicious events.

Recovery

Restore Data: Recover lost or corrupted data due to an attack.

Restore Services: Re-establish interrupted services as quickly as possible after an attack.

Maintain Audit Logs: Keep records of all actions performed on the system, including those by administrators, to assist in forensic investigations.

Security Patterns

Security patterns are reusable solutions for common security problems. They describe a general approach to protecting the system against a specific type of threat. Some common security patterns include:

Two-Factor Authentication (2FA): Requires users to provide two forms of authentication, such as a password and a code sent to their phone, to access the system.

Role-Based Access Control (RBAC): Defines different levels of access to the system based on user roles.

End-to-End Encryption: Protects data in transit, ensuring that only the intended sender and recipient can decrypt it.

Web Application Firewall (WAF): A firewall that protects web applications from common attacks such as cross-site scripting (XSS) and SQL injection.

Intrusion Detection System (IDS): A system that monitors network traffic for suspicious activities and generates alerts when something is detected.

Practical Examples of Technologies, Tools, or Services

Various technologies and tools can be used to implement the mentioned security patterns and tactics:

AWS Security Hub: Service that aggregates and analyzes security data from various AWS services, such as Amazon GuardDuty, Amazon Inspector, and AWS Firewall Manager.

Azure Security Center: Unified cloud security platform that provides security monitoring, threat analysis, and security recommendations for Azure resources and hybrid environments.

Google Cloud Security Command Center: Platform that provides unified visibility and control over Google Cloud’s security posture, including threat detection, vulnerability management, and security policy management.

Snort: Network intrusion detection system (NIDS) used to detect attacks and malicious activities in real-time.

OpenVPN: Open-source VPN solution that can create secure connections between networks and devices.

Ossec: Host-based intrusion detection system (HIDS) used to monitor log files, file integrity, and system activities for evidence of malicious activities.

Keycloak: Open-source identity and access management platform supporting standard protocols like OpenID Connect, OAuth 2.0, and SAML 2.0.

Splunk: Data analysis and security monitoring platform used to aggregate, analyze, and visualize security data from various sources.

Cisco ASA: Next-generation firewall offering advanced security features such as intrusion prevention, URL filtering, and VPN.

Microsoft Active Directory: Directory service providing identity and access management for Windows networks.

Hashicorp Vault: Secrets management tool used to securely store and access confidential information such as passwords, certificates, and API keys.

Testability in Software Architecture

Testability refers to the ease with which defects in software can be demonstrated through tests, typically based on execution. A well-defined software architecture can reduce development costs by making testing easier, more efficient, and more effective.

Scenario for Testability

A common scenario for testability involves a developer who, upon completing a unit of code, runs a sequence of tests. The effectiveness of these tests, measured by code coverage and the time required for execution, determines the software’s testability.

Stimulus Source: Vehicle tracking system development team.

Stimulus: Completion of the implementation of a new software module in the tracking system, responsible for recording and analyzing driver behavior related to harsh braking and sudden acceleration.

Environment: Development and testing environment, using a simulator that replicates vehicle and sensor behavior.

Artifact: The newly implemented software module, which integrates with the existing tracking system.

Response: The development team uses a testing framework that injects simulated data into the new module, simulating different driving scenarios (harsh braking, sudden accelerations, sharp turns). The framework allows control of the module’s inputs (sensor data) and monitors its outputs (generated alerts, telemetry data).

Response Measure:

- Code Coverage: The testing framework measures the percentage of lines of code in the new module exercised during tests, aiming for high coverage to ensure software quality.

- Number of Defects Found: The framework records and classifies defects found during testing, allowing the development team to fix them before production deployment.

- Test Execution Time: Short execution time for tests enables faster development cycles, facilitating continuous integration and continuous delivery (CI/CD).

- Ease of Replicating Failures: The testing framework should allow easy reproduction of specific scenarios that caused failures in the new module, aiding in debugging and error correction.

Use Case

The developer completes a unit of code during development and runs a sequence of tests, the results of which are captured and provide 85% path coverage within 30 minutes.

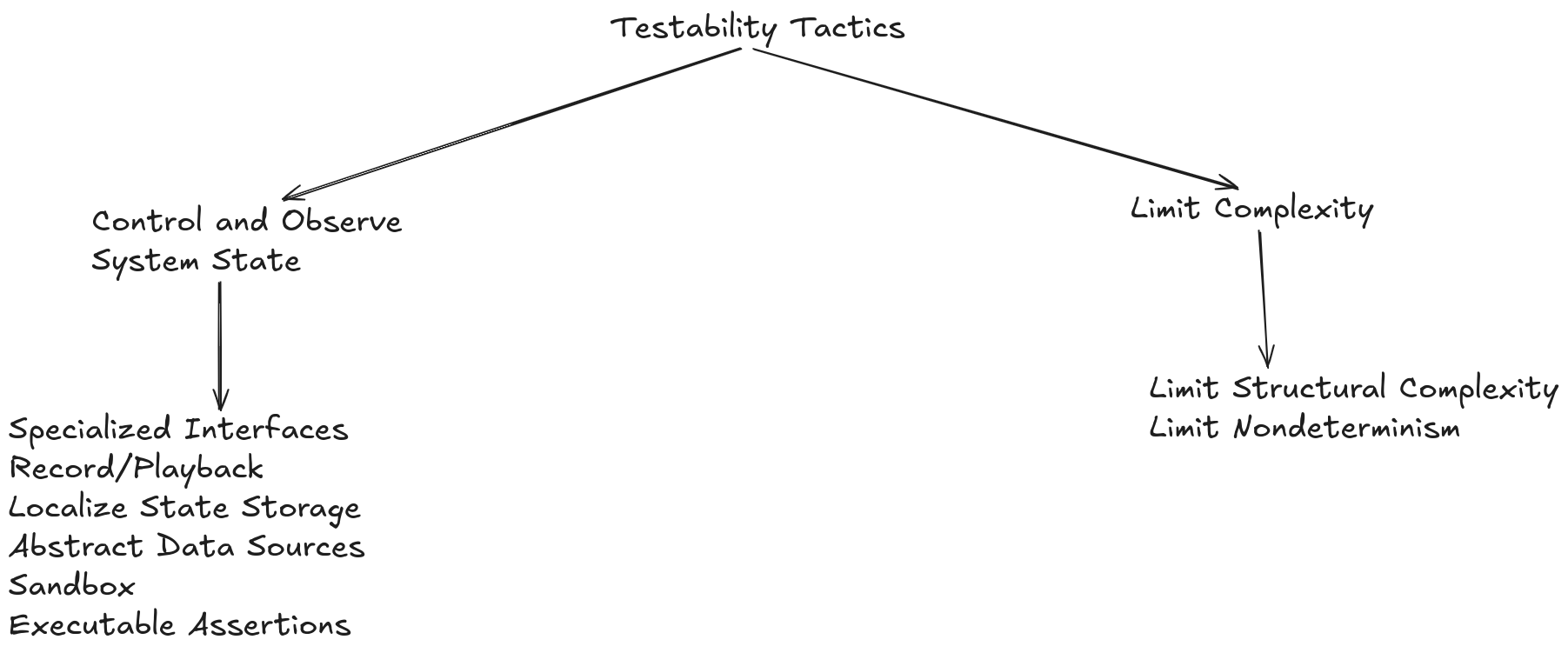

Tactics for Testability

Tactics for increasing testability can be divided into two main categories:

Controlling and Observing of System State: Focuses on making the system’s behavior more transparent and manageable during testing.

Limiting Complexity: Complex systems are inherently difficult to test due to the large number of possible states and interactions between components.

Control and Observation of the System State

Specialized Interfaces: Allow testers to control and observe the internal state of a component.

Logging/Replay: Enables the reproduction of specific test scenarios by recording and replaying interactions with the system.

Locate State Storage: Facilitates observation and manipulation of the system state by isolating data storage.

Abstract Data Sources: Replaces real data sources with controlled alternatives for testing.

Sandbox: Allows isolated testing by replicating a controlled production environment.

Executable Assertions: Incorporates checks into the code to identify failure states during execution.

Limit Complexity

Limit Structural Complexity: Reduces the complexity of the system, making it easier to understand and test individual components.

Limit Non-Determinism: Reduces unpredictable system behavior, facilitating the reproduction and testing of scenarios.

Testability Patterns

Strategy Pattern: Allows the replacement of algorithms or behaviors at runtime, making it easier to test different implementations.

Observer Pattern: Notifies testers about changes in the system state, facilitating the observation of system behavior during tests.

MVC (Model-View-Controller): The clear separation between data (Model), user interface (View), and business logic (Controller) simplifies the testability of each component.

Practical Examples of Technologies, Tools, or Services for Testability

JUnit: A framework for writing and running automated tests in Java. Supports creating isolated test environments (Sandbox) and implementing executable assertions.

Mockito: A library for creating mock objects in Java, useful for abstracting external dependencies during testing.

Selenium: A tool for automating user interface tests in web browsers. Allows recording and replaying user interactions (Recording/Reproduction).

Docker: A platform for creating, deploying, and running applications in containers. Facilitates creating isolated test environments (Sandbox) that mirror the production environment.

Kubernetes: A container orchestration system that automates deployment, scaling, and management of containerized applications. Useful for deploying and managing complex test environments.

Usability in Software Architecture

Usability refers to how easily a user can perform a desired task using a system and the support provided during interaction. A system with high usability is intuitive, easy to learn, and pleasant to use.

Scenario for Usability

The general usability scenario involves a user interacting with a system to achieve a specific goal. Usability is measured by the effectiveness, efficiency, and satisfaction of the user during this interaction.

Example Usability Scenario: A user wants to buy a product from an online store. The system should allow the user to find the desired product, add it to the cart, and complete the purchase quickly, easily, and intuitively.

Stimulus Source: A logistics manager needs to set up a new alert in the tracking system to notify them when a vehicle enters a specific area on the map, indicating a potential unauthorized delivery.

Stimulus: The logistics manager wants to configure the new alert quickly and intuitively, without the need to consult complex manuals or tutorials.

Environment: The logistics manager is using a responsive web interface to access the tracking system from their desktop computer.

Artifact: The web interface of the vehicle tracking system.

Response: The web interface of the tracking system provides an alert configuration wizard with a user-friendly graphical interface. The wizard guides the logistics manager through simple steps: selecting the type of alert (“geofence alert”), drawing the area on the map using an intuitive drawing tool, setting the alert parameters (monitored vehicles, activation times), and naming the alert.

Response Measure:

- Time to Configure the Alert: The logistics manager should be able to set up the new alert in less than 5 minutes without assistance.

- Number of Errors During Configuration: The logistics manager should be able to configure the alert making fewer than 2 errors.

- User Satisfaction: After setting up the alert, the system prompts the manager to rate their experience using a usability scale, with options ranging from “very difficult” to “very easy.”

Use Case

The user downloads a new app and uses it productively after 2 minutes of experimentation.

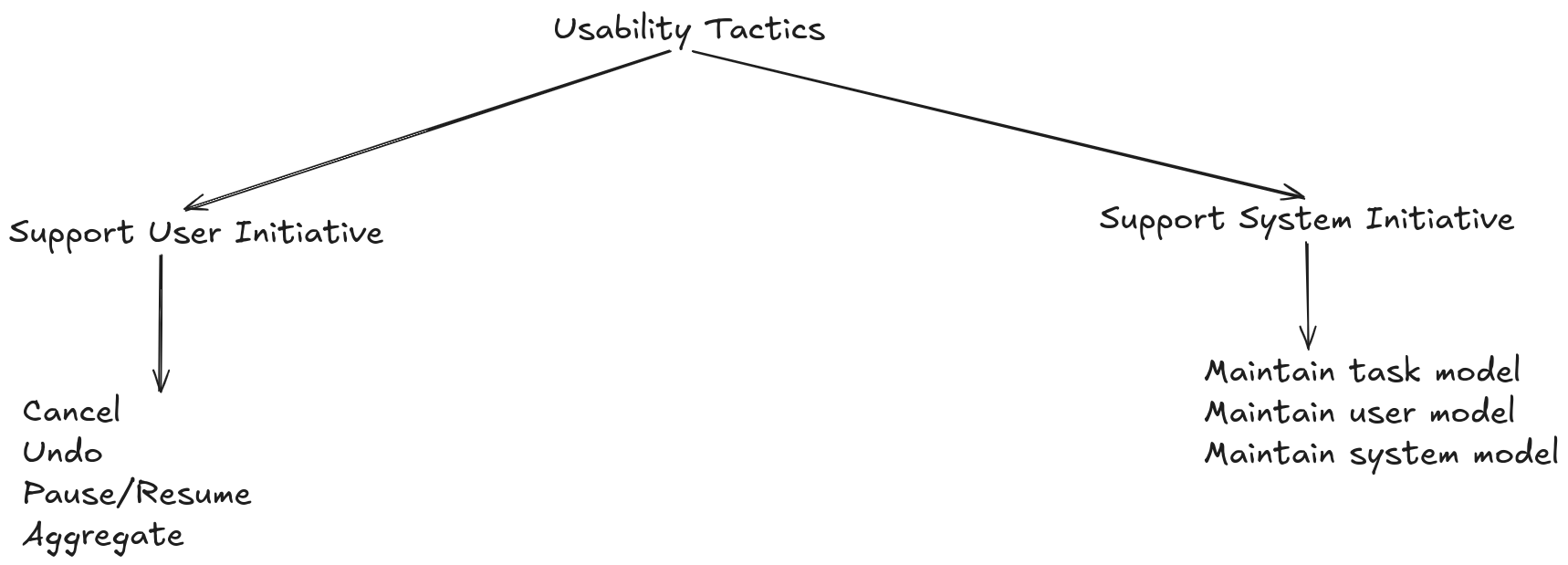

Tactics for Usability

User-Initiated Support: Focuses on providing users with the tools to interact with the system efficiently and intuitively, responding to their actions and allowing for error correction.

System-Initiated Support: The system takes a more proactive role, using models to predict user behavior and provide assistance or feedback.

Maintain a Task Model: Understand the tasks users want to perform with the system.

Maintain a User Model: Create personas and use cases to represent different types of users and their needs.

Maintain a System Model: Ensure that the user interface accurately represents the user’s mental model of the system.

Provide Clear and Concise Feedback: Keep users informed about the system’s status and the progress of their tasks.

Prevent Errors: Eliminate or minimize the possibility of user errors through intuitive design and input validation.

Provide Help and Documentation: Offer users easy access to useful information about the system, such as tutorials and FAQs.

Usability Patterns

MVC (Model-View-Controller): Separates business logic from the user interface, making the system easier to modify and test.

Observer Pattern: Allows objects to notify other objects about state changes, facilitating real-time updates to the user interface.

Memento Pattern: Allows saving and restoring the previous state of an object, useful for implementing functionalities like “undo” and “redo.”

Practical Examples of Technologies and Tools for Usability

Front-End Frameworks (React, Angular, Vue.js): Facilitate building interactive and responsive user interfaces, implementing the MVC pattern.

Prototyping Tools (Figma, Adobe XD): Allow the creation of interactive prototypes to test the usability of the user interface before development.

State Management Libraries (Redux, MobX): Assist in implementing the Observer Pattern, making it easier to update the user interface in response to changes in application state.

Conclusions

The only certainty we have when building software is that it will encounter problems and inevitably fail at some point. Shedding the blame and evolving from errors and learnings is an important part of the software lifecycle and even intrinsic to human nature. Learning from these and systematically constructing the elements that make up software using engineering practices can smooth the problem-solving process and pave the way for potential (and very likely) changes, adjustments, and evolutions that the software will undergo throughout its lifetime.

Although some choices are based on common knowledge or influenced by biases, employing widely tested techniques, concepts, and tactics from numerous companies is essential. This not only saves time and money but also results in a robust software architecture that remains aligned with its purpose. Ignoring this model can indeed determine the life or death of a company in the competitive market today.

Identifying and addressing functional and non-functional requirements from a business desire, often guided solely by intention, poses an intrinsic challenge in software development. This difficulty arises from the fact that merely conceiving a desire does not, by itself, provide the detailed specifications needed to materialize an efficient, reliable, and secure system.

The task of translating the abstract vision of a desire into concrete requirements that guide the construction of a system requires careful analysis, structured methods, and a deep understanding of the business need and its purpose. The absence of clear and well-defined metrics increases the complexity of this phase, demanding additional effort in seeking solutions that meet the often implicit expectations of the business.

And finally, some say that Software Architecture is the “art of taming complexity,” and I couldn’t agree more with that statement.

Useful links

If you came across this article through a presentation, you can find the presentation deck here

References

Software Architecture in Practice, Fourth Edition

Any sugests or doubt?

Feel free to reach out to me on social media: twitter ,linkedin and github.

You can also email me directly at rmnobarra@gmail.com.

Support

Did you really enjoy my content? Consider buying me a coffee through my Bitcoins wallets:

Bitcoin Wallet:

bc1quuv5hml9fjkf7azgwkt4xp867pzdwzyga33qmj

Lighting Address:

lnbc1pjue6mkpp5yj737e7fm6efhlj6sns42a875pmkencqmvdshf4ghlnntaet5llsdqqcqzzsxqrrsssp5d9hxl686w839qkwmkm0m30cf5gp4gnzxh68kss393xqzlsg0wr3q9qyyssqp3933zc3fg46nk3vafh63r3lqd0jn2p04w5xrz77h33rrr3xm7ckegg6s2ss64g4rf4jg87zdjzkl5tup7umqpghy2qnk65tqzsnplcpwv6z4c

Bye!